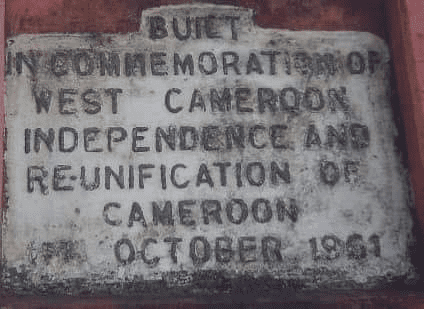

The date of October 1, 1961 is one of the fundamental dates in the history of our country, and the future of our nation.

Unfortunately, the successive regimes of Ahmadou Ahidjo, and that of his successor Paul Biya, have ruled otherwise. As a result, no one celebrates it anymore. And yet it marked the reconstitution, albeit partial, of our homeland divided in two by the French and British colonialists on March 4, 1916, after their respective troops invaded our country, and waged a two-year war against France. German colonial army, which resulted in an incalculable number of Cameroonian deaths “can we read in one of the myriad of writings of the historian and politician Enoh Meyomesse.

This October 1, Cameroon celebrates at least in the writings its unification (Anglophone and Francophone Cameroon). An anniversary which occurs each time when the English-speaking question resurfaces, where positions are becoming more and more radical on the subject of the future of the nation while leaving three identity positions unresolved: The followers of a purely state independent, an idea defended by the secessionists. Another group who dream of a return to a federal state and finally those who think of autonomy. These different positions continue to fuel the debates over the years

This problem dates back to 1961 when the political elites of two territories with different colonial legacies, one French and the other British, agreed to form a federal state. Contrary to the expectations of Anglophones, federalism has not allowed for strict parity in terms of their cultural heritage and what they consider to be their Anglophone identity. It turned out to be only a transitional phase in the full integration of the English-speaking region into a highly centralized unitary state.

To date, the successive events that have occurred on the date of the 49th anniversary of the reunification in 1961 of Anglophone and Francophone Cameroon within the same federation, crudely recall the difficulties of the Cameroonian legislator in consolidating his nation-state project.

Questions of identity colors continue to divide the country and the symbiosis is struggling to settle between the two cultural entities. This view is only made possible if we take a retrospective look at the history of this country.

By the treaty of July 12, 1884, Cameroon had become a German protectorate. This country will be successively under the mandate of the League of Nations in 1918 and under the supervision of the UN on December 19, 1946 and administered respectively by France and Great Britain.

These two colonizing powers will imprint their policy in the management of the two Cameroonians.

Cameroon, divided into two zones, thus becomes an object of international law. From then on, a mission will be assigned to France and Great Britain by the UN. It is to prepare Cameroonians for advanced autonomy and total independence with strict respect for human dignity and fundamental freedoms. Appearing as a state entity, it obtained its independence on January 1, 1960. (1)

Already in 1959, in resolution 1350 (XIII) of March 13, 1959, the United Nations General Assembly requested that the administrative authority of Cameroon organize, under the supervision of the United Nations, separate plebiscites in the northern part and in the southern part of Cameroon under British administration “in order to determine the aspirations of the inhabitants of the territory regarding their future”. These separate plebiscites, organized on February 11 and 12, 1961, were won by supporters of unification by 237,575 votes against 97,741 votes for rallying in Nigeria.

From these results obtained, a constitutional project will come to give precedence to a federal state with a very centralized constitution instead of an autonomous province as desired by the English-speaking public.

The two federated states then merged into a united Republic after a referendum in 1972, before the country took its current name of Republic of Cameroon with the accession of Paul Biya in 1982. The country had thus completed the process of dismantling of the “Federal Republic of Cameroon”, which brought together the Anglophone and Francophone States inherited from the military victory of the “Allies” over the German colonizer, in 1916. (2)

On May 20, 1972, at the initiative of Ahmadou Ahidjo, then President of the Federal Republic, a referendum was organized in Cameroon. A single question is asked of Cameroonians (English and French speakers): “Do you approve, in order to consolidate national unity and accelerate the economic, social and cultural development of the nation, the draft Constitution submitted to the Cameroonian people by the President of the Federal Republic of Cameroon and establishing a Republic, one and indivisible, under the name of United Republic of Cameroon? “At the end of the vote, the” yes “largely won. This is how” Southern Cameroon “found itself involved in February 1972 in the formation of a centralized unitary state.

For Enoh Meyomesse “It was on May 20, 1972 that the Ahidjo regime put an end to the celebration of the date of October 1, 1972. The reason? France having ordered him to put an end to federalism in Cameroon because it had just decided to start the exploitation of Cameroonian oil which was in Western Cameroon and feared a secession on the part of the English-speaking community, he carried out his rigged referendum of May 20, 1972, during which, the Cameroonians did not found, in the polling stations, only two types of ballots: the “YES”, and the “YES.” Naturally, the “YES” won in a “brilliant” way (3)

During Ahidjo’s reign and even today, Cameroon enjoys a linguistic and cultural richness which is bilingualism (French-English).

In 1984, Ahmadou Ahidjo’s successor at the head of the United Republic of Cameroon, Paul Biya, had the Constitution amended by removing the term “united”. For a group of nationals of the former English-speaking Cameroon, “it is an act of secession, which withdraws the Republic of Cameroon (Editor’s note, former name of French-speaking Cameroon) from the unitary state”.

Today, secessionist demands are debated in a climate of social tensions and war. Several movements have been created to claim their solidarity with a part of the country which considers itself wronged by the central authority.

Since then, President Biya has never succeeded in calming the frustrations of the North-West and South-West regions which feel marginalized in favor of the eight French-speaking regions. These frustrations created a breeding ground for a secessionist current which became radicalized during the 1990s, passing from the simple demand for a return to federalism to that of pure and simple independence, very often with sudden outbreaks of fever.

The secessionists believe that within the framework of the unitary state, the various governments give pride of place to Francophones, whether in socio-economic development or in the management of human resources. Hence their decision to maintain the Southern Cameroons National Council (SCNC), a sort of assembly representative of the interests of Anglophones. She even accuses the UN of having failed with regard to the English-speaking populations of Cameroon.

Apart from the secessionist threat, National Unity today suffers from the effects of tribalism. Cameroon, would have more than three hundred languages, that is to say as many ethnic groups. Ahmadou Ahidjo’s regime has played on regional balances, adopting, for example, at the level of education, a policy of two weights, two measures.

National Unity, we can say today, is holding up difficult, because the majority of Cameroonians are no longer attached to it. It would be threatened by the political struggles which never cease to engulf the small faults that it presents, the better to destroy its dynamic.

Whether for the Anglophone problem or for interethnic wars, in the politician, there is the motive. The politician can cease to be a danger if he evolves in a truly democratic system, which does not encourage cheating and manipulation. This is not yet the case in Cameroon.

To try to find a solution to identity and separatist claims in our country, it would be necessary to strengthen local democracy, for example, by electing municipal officials by direct suffrage as well as that of regional governors.

We can also think of decentralization, that which allows the Cameroonian populations to participate in the management of their territorial entity so that everyone feels concerned by the life of their region and necessarily by the life of Cameroon.

Dialogue appears as an alternative to secessionist, autonomist and independence tendencies in Cameroon.

For a power that does not particularly have the reputation of negotiating with its opponents, it is time to speak with dissent because, this will be a step forward whose impact cannot be minimized, nor the scope, let alone the impact.

The Anglophone problem is Cameroon’s and it would certainly be a mistake for the authorities to think that it is first the “Anglophone problem” that should first be dealt with ethnically and linguistically.

If under other skies the dialogue prevailed in the management of the important questions why not think about it in Cameroon? This option would benefit from being used in a winning synergy for the cultural, social and economic stability of the country. (4)

Bibliographies: (1) Histoire du Cameroun, F David, editions Carougep 156. (2) Democratic transitions in Cameroon from 1990 to 2004, Francine Bitéé, Editions l’harmattan. (3) Enoh Meyomesse, analysis published on camer.be on October 1, 2008. (4) Notes from the Hugues SEUMO research briefs collections to be published (Editions Bajag-Meri-Paris)